By Chuck Maker, DVM

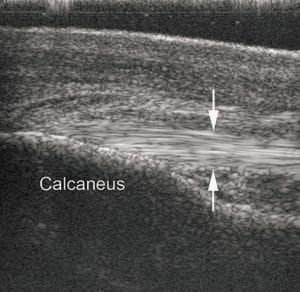

An 8 year old warmblood mare used for dressage pulled up acutely lame in her left hind limb after cross country at her last event and developed a marked swelling below the point of her left hock within a few hours. While her degree of left hind lameness was only slight, this mare resented deep palpation of the swelling below her left hock. She became lamer following sustained flexion of the hock. An ultrasonogram revealed tearing of the plantar ligament (PL) diagnosing plantar ligament Desmitis or “curb”.

An 8 year old warmblood mare used for dressage pulled up acutely lame in her left hind limb after cross country at her last event and developed a marked swelling below the point of her left hock within a few hours. While her degree of left hind lameness was only slight, this mare resented deep palpation of the swelling below her left hock. She became lamer following sustained flexion of the hock. An ultrasonogram revealed tearing of the plantar ligament (PL) diagnosing plantar ligament Desmitis or “curb”.

“Curb” refers to any swelling at the back of the hock. Soft tissue structures located there, include skin, subcutaneous connective tissue, deep and superficial digital flexor tendons and the plantar ligament. Trauma to any of these structures ‘can create a convex profile at the back of the hock. For accurate treatment and prognosis, it’s critical to use diagnostic imaging to specifically identify the damaged tissue. In this case, ultrasonography proved to be diagnostic and afforded us an accurate diagnosis and necessary treatment.

We treated this patient with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, topical DMSO/corticosteroid and an exercise regimen of rest with daily walking. After six weeks, the mare resumed training. Give us, Alpine Animal Hospital, a call at 963.2371 if you have any gait or lameness concerns on your sport horse.

We treated this patient with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, topical DMSO/corticosteroid and an exercise regimen of rest with daily walking. After six weeks, the mare resumed training. Give us, Alpine Animal Hospital, a call at 963.2371 if you have any gait or lameness concerns on your sport horse.

A well-bred eight (8) year old mare pulled up severely lame in her right front leg three (3) weeks after her last shoeing. She had been sound the previous night when fed in the stall, but had swelling around her hoof with palpable heat the following morning.

Her degree of lameness was quite severe (almost non weight bearing) necessitating an examination before regular business hours for fear she had somehow fractured her foot or distal limb in the stall. On examination the mare resented deep palpation of the swelling at her heel bulb and was extremely sensitive to an area across the front of the toe. She had a bounding digital pulse and the foot was warmer than the other forelimb. She had been out on early spring green grass and was known to typically have thin soles by the farrier and owner. Removal of the shoe initially did not present any drainage or signs of an abscess. Removal of additional sole was avoided due to her history of thin soles. After the shoe was removed and the sole of the foot pared, a digital radiograph was taken to rule out the possibility of a coffin bone fracture or spring green grass laminitis from a potential solar abscess.

Parallel alignment was seen on the lateral x-ray at right. A small gas density was noted along the solar aspect of the coffin bone of the foot which indicated the likelihood of infection and an abscess. Further debridement of the white line elicited drainage of a sole abscess. The mare was successfully treated with oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, topical DMSO/nitrofurazone gel bandages and daily Epsom salt soaks before reshoeing in one week. After 10 days the mare resumed training.

Parallel alignment was seen on the lateral x-ray at right. A small gas density was noted along the solar aspect of the coffin bone of the foot which indicated the likelihood of infection and an abscess. Further debridement of the white line elicited drainage of a sole abscess. The mare was successfully treated with oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, topical DMSO/nitrofurazone gel bandages and daily Epsom salt soaks before reshoeing in one week. After 10 days the mare resumed training.

Foot abscesses usually develop at an area of separation of the horny outer layer of hoof wall from the softer underlying layer of the hoof, often at the white line. Dirt accumulates in these cracks and the area soon becomes infected. Such infections can be quite advanced before the abscess affects the sensitive part of the foot, causing pain. Hence, pain from an abscess can develop suddenly, such as soon after shoeing or during mud season or even after a hard workout. Drainage is the primary means of treating a foot abscess. Softening or “drawing” of the infected area and cleanliness are also important and done with alternating hot soaks in water and Epsom salts and application of bandages with ointments intended to draw out infection such as ichthamol, MG 60 or as in this case Nitrofurazone and DMSO. Thereafter shoeing with a pad was necessary to protect the sensitive tissues of the foot from becoming contaminated and infected until the sole healed.

Foot abscesses usually develop at an area of separation of the horny outer layer of hoof wall from the softer underlying layer of the hoof, often at the white line. Dirt accumulates in these cracks and the area soon becomes infected. Such infections can be quite advanced before the abscess affects the sensitive part of the foot, causing pain. Hence, pain from an abscess can develop suddenly, such as soon after shoeing or during mud season or even after a hard workout. Drainage is the primary means of treating a foot abscess. Softening or “drawing” of the infected area and cleanliness are also important and done with alternating hot soaks in water and Epsom salts and application of bandages with ointments intended to draw out infection such as ichthamol, MG 60 or as in this case Nitrofurazone and DMSO. Thereafter shoeing with a pad was necessary to protect the sensitive tissues of the foot from becoming contaminated and infected until the sole healed.